The Socioeconomic Impact on the UK’s Value-Added Tax on School Fees

Author: Zifu Yang

September 19, 2025

Approximately 6–7 percent of all pupils in the United Kingdom receive private education, yet this group accounts for a disproportionate share of highly influential jobs in the nation.1 Many factors contribute to this disparity, but one stands out in particular: their type of education.

To address growing concerns over equity in the nation, the UK government has decided to introduce a 20 percent Value-Added Tax (VAT) on all education and boarding services provided by private schools, further reallocating the tax revenue to improve the quality of public education. This essay argues that, if implemented correctly, the private education tax reform can positively impact socioeconomic mobility, levelling the educational playing field between private and public sectors.

Private schooling is a significant contributor to socioeconomic inequality in the UK.2 Research shows that students in the private sector score higher than their state counterparts in exams,3 giving them a competitive advantage when applying to higher-status universities. Combining better educational attainment and university education, private school students earn more in later life than their state-educated counterparts.

Figure 1 shows how enrollment at private schools in the UK has historically remained highly skewed towards high-income households,4 raising concerns about intergenerational inequality and socioeconomic mobility for households unable to afford private school education.5

Figure 1. Income Concentration of Private School Participation, 1997-20184

When comparing the long-term outlook for students from different educational systems, studies show that private school students earn a higher wage premium compared to their state-educated counterparts,6 providing evidence of income disparity in figure 2. At age 25, the wage premium was 17 percent in 2015 with little gender difference;7 by age 42, it rose to 21 percent for women and 35 percent for men in the 1970 cohort.8

Figure 2. Private School Wage Premiums (Percent)6

More concerning is that poor education plays a significant role amongst interconnected factors that perpetuate generational poverty in the UK.9 Consider the poverty cycle diagram in figure 3. As shown, a lack of education and skills reduces employment opportunities and earning potential. Poor educational outcomes are both a result and cause of vicious, inescapable poverty traps.11 Moreover, simply receiving education is not sufficient to break the poverty cycle; it is the quality of education received that matters most.12

Figure 3. The Poverty Cycle10

Reports have shown that improvements in educational outcomes are strongly linked to reductions in poverty incidence.13 Therefore, targeted investments in education can lead to improvements in educational outcomes, which would enable a reduction in poverty for low-income and disadvantaged households,12 thereby enhancing socioeconomic mobility. Experts have also suggested that policies aimed at equalising education quality could, over time, help narrow initial inequalities.14

According to reports published by the UK Treasury, imposing VAT on private school fees is set to generate £1.8 billion in annual revenue by the 2029-2030 fiscal year, which the government has pledged to invest in its entirety to expand early years childcare in the form of 3,000 new nurseries, rolling out breakfast clubs for all primary schools, recruiting 6,500 new teachers to support the state sector, and improving teacher training.15 Assuming the tax revenue is perfectly distributed with no external leakages and average private school tuition fees remain constant, the funding could improve socioeconomic mobility by raising the quality of public education and generating positive externalities for society.

According to Becker’s theory of human capital, education is viewed as an investment in future productivity. Firms will subsequently depend on investments in human capital to increase competitiveness, leading to productive workers receiving greater pay.16

The government’s plan to use tax revenue to hire an additional 6,500 teachers would lead to a direct increase in the student-teacher ratio of public schools, theoretically improving productivity in state schools. Moreover, increased staff and productivity are expected to enhance the quality of education in the public sector, thereby enabling all pupils, including those from disadvantaged backgrounds, to access quality education.

Various studies have also shown that school quality has a positive causal effect on student earnings.17 As a result, a surge in pupils receiving quality education results in a more productive population, and, following economic theory and research, will thus increase their later-life earnings. In theory, this will effectively narrow the income gap between individuals educated in public and private schools, promoting greater socioeconomic mobility over time.

It is also important to note that between 2015/16 and 2023/24, secondary pupil numbers in state schools increased by 15 percent, while teacher numbers rose disproportionately by just 3 percent, resulting in larger classes and greater pressure on staff.18 Combined with the fact that secondary teacher training recruitment in 2024/25 reached only 62 percent of the Department for Education’s target, this shows signs of a teacher shortage in the UK.18 Thus, hiring 6,500 teachers in the state sector could theoretically address this labour shortage and lead to greater socioeconomic mobility for disadvantaged pupils through more equitable access to high-quality teachers.

In the long run, as more resources are allocated to the public sector over time, middle- and high-income households may become more inclined to transition from private to public sector education, thereby improving socioeconomic diversity in the state sector. Thus, this could have a positive impact on socioeconomic mobility through improved networking and other external factors, as well as student attainment, which could ultimately lead to higher later-life earnings.19

From an aggregate perspective, greater accessibility of quality education for those in poverty, along with higher-quality teachers, have been linked to productivity gains,20 which would enhance the UK population’s collective productivity and, thus, its workforce competitiveness in the long run. Given that improvements in education quality and thus productivity of labour are key determinants of an economy’s aggregate supply (AS), a more capable workforce will cause an outward shift in the UK’s LRAS in figure 4, which, coupled with a possibly greater inflow of foreign investment, can potentially fuel economic growth in the UK.21 Assuming ceteris paribus, economic growth in the UK can lead to a direct improvement in socioeconomic mobility nationwide22 in the form of rising income per capita, income growth, and other economic indicators.23 Greater spending in the economy can also generate more tax revenue, which could then be reinvested in further improving state education or other sectors of the economy with socioeconomic benefits, such as public services like healthcare.

Figure 4: Shifts in UK’s AS Curve

As middle-class families shift their children to the public sector, proponents of VAT on private school fees have raised concerns about a possible influx of students, potentially causing increased strain on the public education system as a whole.

It is important to note, however, that the price elasticity of demand (PED) of private schooling is relatively inelastic due to factors such as values, culture, and connotation, leading to a higher degree of necessity amongst households. Empirical research also shows that, despite a 20 percent real-terms rise in school fees since 2010, the share of pupils in private schools has remained steady at 6–7 percent.24 As a result, an increase in private school fees is projected to have a marginal impact on the number of students expected to join the public sector in the long run, approximately 35,000 according to the government. Despite this representing only a tiny proportion of overall pupils in the public sector shown in table 1,25 pupils transitioning from private to public schools will inevitably lead to additional costs, which the government estimates to be around £270 million in the long run–though the projected £1.5–1.7 billion per annum revenue generated by VAT heavily outweighs the added costs.

Additionally, considering that 82 percent of all state-funded schools in the UK were under enrollment capacity in 2023/2426 and that the majority of transitions take place at natural points in a pupil’s educational journey (e.g. primary to secondary), the public sector should be able to accommodate new students without experiencing significant strain on school resources, especially after factoring the 6,500 newly-hired teachers in the government’s plan.

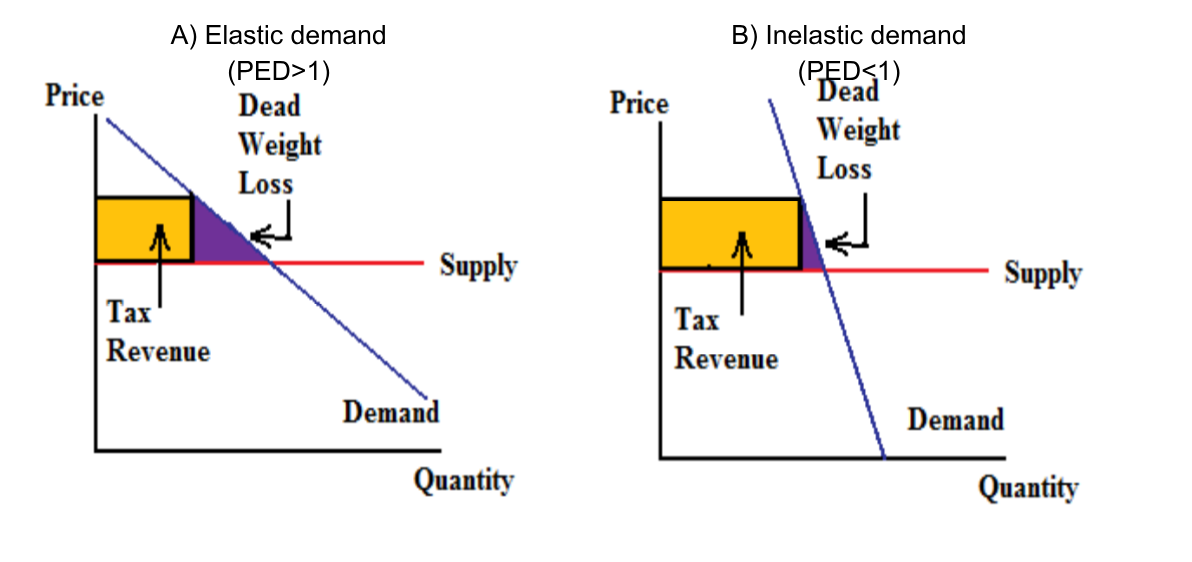

However, Ramsey’s theory of optimal taxation states that, assuming a perfectly elastic supply curve, the optimal amount of taxation a government should impose is dependent on the good’s PED (price elasticity of demand); the more elastic the PED is, the smaller the optimal tax.28 As such, the inelastic PED of private education in the UK, according to economic theory, should be subject to higher-than-average taxation to minimize distortionary effects on efficiency while also maximising revenue, such that there is minimal impact on the private sector as shown in figure 5. Research shows, however, that setting differentiated taxes is likely to have minimal benefits compared to a wide, simple base VAT, thus justifying the level of taxation on private school education.29

Figure 5. Effect of PED on Dead-Weight Loss27

Of course, as one study puts it, simply pouring money into education does not automatically equate to lower socioeconomic inequality.30 This is because critics have argued that improving the quality of public sector education is insufficient in eradicating systemic biases that favour private school students in the workforce.

Perhaps the benefit of private education lies in its signal to employers. Signalling theory suggests that schooling serves as a signal of productivity to employers, rather than solely building human capital.31 Empirical research also indicates that signalling comprises at least one-third of education’s financial rewards.32 This is severely unfair towards state-educated individuals, as, by this logic, a stronger signal from private education should lead to better financial outcomes for an individual, assuming there is asymmetric information between the employer and worker.33

Take Finland’s case. In the 1990s, Finland's education reform transformed all vocational schools into polytechnics, expanding the supply of education to all regions. This change was designed to enhance the quality and perception of vocational education nationwide. Following the reform, polytechnic graduates experienced an increase in their earnings compared to those who had graduated from the same institutions before the reform.34 The outcomes of this reform thus support the signalling model of education, whereby the supposedly “higher quality” polytechnic qualifications served as a stronger signal to employers, which correlates with higher wages.

Although it may be difficult to rid private schools of their connotation in the short term, as more households transition their children into the public sector, more tax revenue will be invested in uplifting teaching quality over time. An improved perception of public schooling could lead to household behavioural changes in the long run, diminishing the signalling advantage of private education and improving socioeconomic mobility. Most importantly, Finland’s case study suggests that changes in the public perception of education systems are possible.

The government should therefore consider allocating tax revenue to develop stronger signals to employers for state sector students. This could be achieved through improvements in course rigour, extracurricular activities, and greater internship opportunities. Alternatively, the government may choose to directly address the signalling advantage of private schools by developing more ways of demonstrating merit or supporting education-blind hiring processes to promote equity.35 Additionally, as government investment in adult skills is comparatively low by international standards and has been declining in both quantity and quality over time, greater funding for the UK’s Adult Skills Fund could enable people from lower socio-economic backgrounds to access better training. This may lead to higher wages and, in the long run, greater socio-economic mobility.36

In all, imposing VAT on private school fees is likely to have a positive effect on socioeconomic mobility in the UK. However, the extent of this impact is dependent on external factors, such as the aforementioned systemic biases towards private education and PED. Therefore, tax revenue investments should target the barriers that hinder disadvantaged individuals from improving their social mobility, while striking a balance between equity and efficiency trade-offs. With these changes, a significant increase in children’s long-term earning potential is possible.

Endnotes

Francis Green,“Private Schools and British Society,” IOE - Faculty of Education and Society, November 29, 2023, https://www.ucl.ac.uk/ioe/research-projects/2023/nov/ private-schools-and-british-society.

David Kynaston and Francis Green, Engines of Privilege: Britain’s Private School Problem. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019.

Morag Henderson et al.,“Private Schooling, Subject Choice, Upper Secondary Attainment and Progression to University,” Oxford Review of Education, November 5, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2019.1669551.

Golo Henseke et al., “Income, Housing Wealth, and Private School Access in Britain,” Education Economics 29, no. 3 (May 4, 2021): 252–68, https://doi.org/10.1080/09645292.2021.1874878.

“ATax Raid on Private Schools Would Attack Social Mobility,” Adam Smith Institute (blog), accessed July 6, 2025, https://www.adamsmith.org/blog/a-tax-raid-on-private-schools-would-attack-social-mobility.

Francis Green, “Private Schools and Inequality,” Oxford Open Economics 3, no. Supplement_1 (July 5, 2024): i842–49, https://doi.org/10.1093/ooec/odad036.

Francis Green et al., “Private Benefits? External Benefits? Outcomes of Private Schooling in 21st Century Britain,” Journal of Social Policy 49, no. 4 (October 2020): 724–43, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279419000710.

Francis Green, Golo Henseke, and Anna Vignoles. “Private Schooling and Labour Market Outcomes,” British Educational Research Journal 43, no. 1 (February 2017): 7–28, https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3256.

“Social Inequality - What Causes Poverty?,” BBC Bitesize, accessed July 6, 2025, https://www.bbc.co.uk/bitesize/guides/zt9hvcw/revision/2.

Tragakes, Ellie. Economics for the IB Diploma with CD-ROM. Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Servaas Van Der Berg et al., “Low Quality Education as a Poverty Trap,” SSRN Electronic Journal, Working Paper no. 25, 2011, https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2973766.

Maria Emma Santos, “Human Capital and the Quality of Education in a Poverty Trap Model,” Oxford Development Studies 39, no. 1 (March 2011): 25–47, https://doi.org/10.1080/13600818.2010.551003.

Pervez Zamurrad Janjua and Usman Ahmed Kamal, “The Role of Education and Health in Poverty Alleviation A Cross Country Analysis,” Journal of Economics, Management and Trade 4, no. 6 (2014): 896–924, https://doi.org/10.9734/BJEMT/2014/6461.

Maria Emma Santos. “Human Capital and the Quality of Education in a Poverty Trap Model,” Oxford Development Studies 39, no. 1 (March 2011): 25–47, https://doi.org/10.1080/13600818.2010.551003.

HM Treasury, Technical Note: Applying VAT to Private School Fees and Removing the Business Rates Charitable Rates Relief for Private Schools. HM Treasury, 2024, accessed July 6, 2025, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/66a7a1bdce1f d0da7b592eb6/Technical_Note_-_DIGITAL.pdf.

Stefan C. Wolter and Paul Ryan, “Apprenticeship,” in Handbook of the Economics of Education, 3 (2011): 521–76, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53429-3.00011-9.

David Card and Alan B. Krueger, Economic Returns to School Quality: A Partial Survey, Working Paper no. 334 (Industrial Relations Section, Princeton University, 1994).

Dawson McLean and Jack Worth, Teacher Labour Market in England: Annual Report 2025 (Slough: National Foundation for Educational Research, 2025), accessed July 6, 2025, https://www.nfer.ac.uk/media/afsn0rmb/teacher_labour_market_in_ england_annual_report_2025.pdf.

Gregory J. Palardy, “High School Socioeconomic Segregation and Student Attainment,” American Educational Research Journal 50, no. 4 (August 2013): 714–54, https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831213481240.

B. Égert, C. de la Maisonneuve, and D. Turner, “Quantifying the Effect of Policies to Promote Educational Performance on Macroeconomic Productivity,” OECD Economics Department Working Papers, no. 1781 (2023), OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/b00051cc-en.

Views top

Copyright © 2023 The Global Horizon 沪ICP备14003514号-6